The Lanyard Board #2 - Towards a Full-Bodied Approach to Analyzing the Seattle Municipal Code

Looking at changes to a living document.

Comparative Analysis Update

I will be leaving the country soon, first to visit friends abroad and conduct an interview for the Disability Commission, and then to Vietnam where the bulk of the Comparative Analysis project’s Vietnamese research will commence. The Lanyard Board will continue to publish while I am abroad, but the exact timing may be fluid - still, expect one full article per week. In other housekeeping matters - this WILL start feeling more like a weekly newsletter, with different segments - but this article is going to be narrowly focused as last week’s was.

TL;DR - Like in genomic analysis, you can look at the whole body of the Seattle Municipal Code and find trends in how ‘variable’ or ‘conserved’ segments are. This could be a good dimension of analysis for understanding the changes to the structure of the city.

The Seattle Municipal Code

The Seattle Municipal Code is usually the first line of attack to understanding Seattle-specific laws. It is the codified form of the ordinances that are passed by Seattle’s City Council, and is extremely well maintained and documented, available here:

For the Comparative Analysis Project I need a model for comparative analysis between cities that is robust, meaningful and consistent. To accomplish this, I will be taking a look at the development of Seattle’s laws that structure its Municipal Government. To further understand this development, I need to understand how and when changes are made to Seattle’s Boards, Commissions, Offices, Departments and Branches.

The easiest way to manage this would be to look through the Seattle Municipal Code for the sections that establish these systems. After all, if you were to look at the database that has the Boards and Commissions listed, you would find that each page diligently denotes the ordinances which establish those bodies, and the Seattle Municipal Code is a codified reference to all of these ordinances. One way to think about it is that looking at the specific ordinances that currently establish these Boards and Commissions can give us a snapshot of what they currently are, but a lot of the historical, developmental and relational information relies on working with the body of law as a whole, best done through the SMC.

The Municipal Code is a tool that can keep the context (having great documentation around revisions) and allow us to ‘zoom in’ and ‘zoom out’ on a given area of City Law. As a living document, the Municipal Code changes as the laws get updated, creating revisions, adding segments and re-arranging codes based on new understanding of where each law slots into the different Titles of the Municipal Code. For the sake of this article, I’ll be looking at the edition of the Seattle Municipal Code that is current as of 1.18.2026.

My main tool for analysis of the Municipal Code will be a relational database that contains the sections of the Charter and Municipal Code, the Ordinance Citations contained in each section and the establishing years for each ordinance that’s cited across the code. The SMC (Seattle Municipal Code) is already segmented by topics, so it makes for a good tool for categorizing and comparing legislation that can match up to similar categorizing efforts in Haiphong, the Comparative Analysis Project’s other municipal subject. More on that later. For today, I’ll be displaying a few of the “first blush” patterns that emerge when you look at ordinances cited across the SMC.

Methodology

Municode, the platform that hosts the Seattle Municipal Code allows exports of the actual text of the Municipal Code by members of the public, located in the “Print or Download Table of Contents” menu (pictured below).

When exported, the result is a .XLSX that contains the municipal code delimited by URL link to each section, the Title of the section, the Subtitle, and the Content (full text). When manipulating the dataset, I had all instances of a standard ordinance citation (“Ord.”) replaced with a special character, and further delimited the data at each point where a standard ordinance citation occurs.

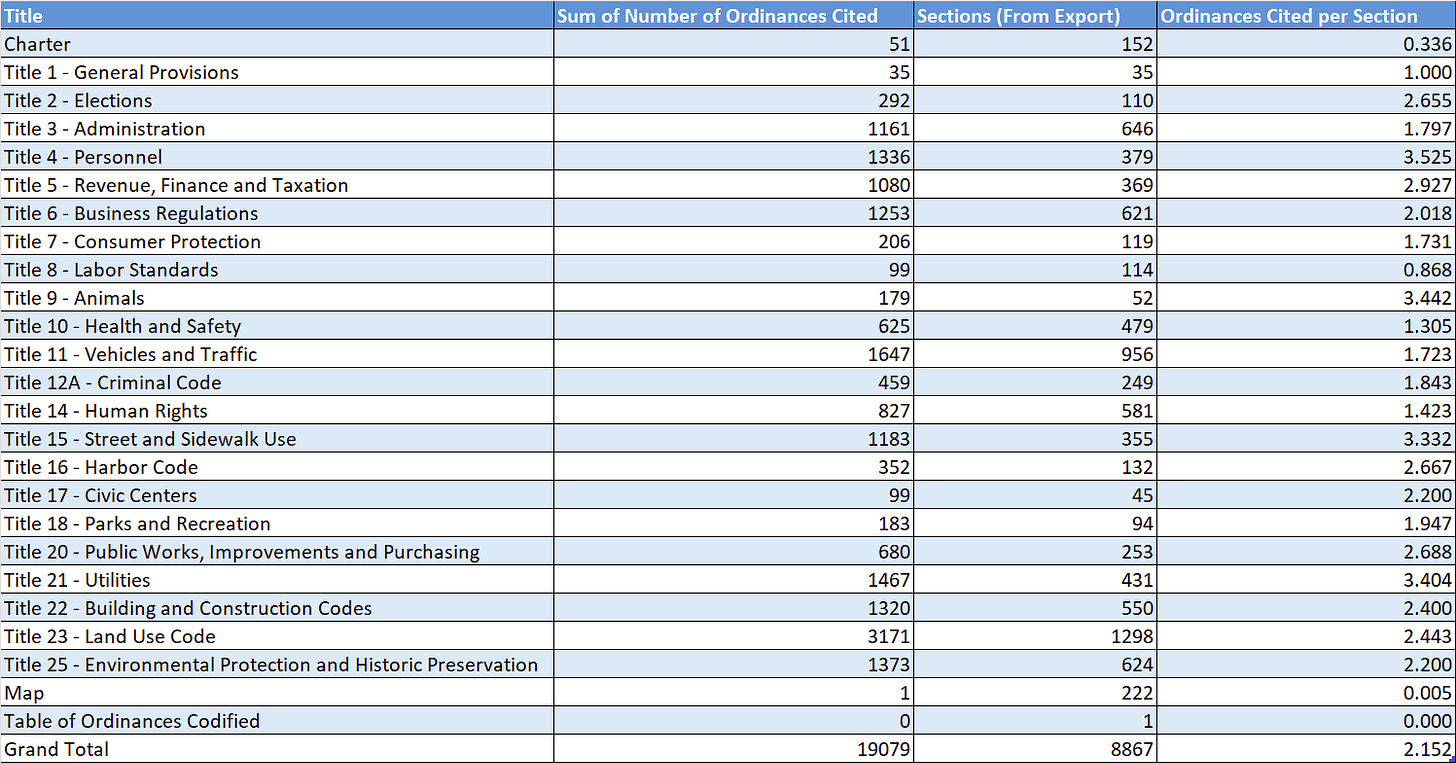

This produces a dataset of 8,867 sections with a maximum of 100 ordinance citations in a section (Belonging to a code related to utility rate discounts) and a minimum of 0 ordinance citations, usually belonging to ‘sections’ that are pulled out which merely state the title of a chapter (as those are exported as their own sections).

The error rate identified for the method used so far sits at around 4.2%. 369 of 8867 sections contain instances of Ordinance Citations not picked up by the normal replacement method due to formatting issues (likely related to the size of the text). A more robust method for catching those will be tried in the future. In addition, a number of headings that aren’t actually “sections” of the code itself are counted as sections, so cleaning this up will increase accuracy.

Today’s analysis will look at the total distribution of ordinance citations across the SMC and comment on possible patterns that can be further investigated.

“Titles”, “Chapters” and “Sections” are terms of the art that are used to describe how the Municipal Code is organized. “Segment” is the general term I’ll use to talk about any set of sections strung together, which may or may not align with the same boundaries as chapters or titles.

Ordinances Across the SMC

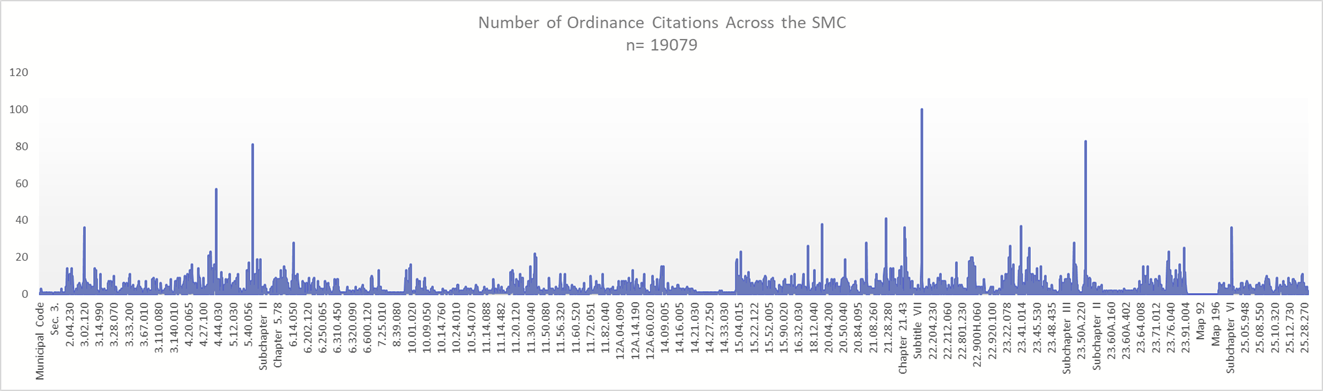

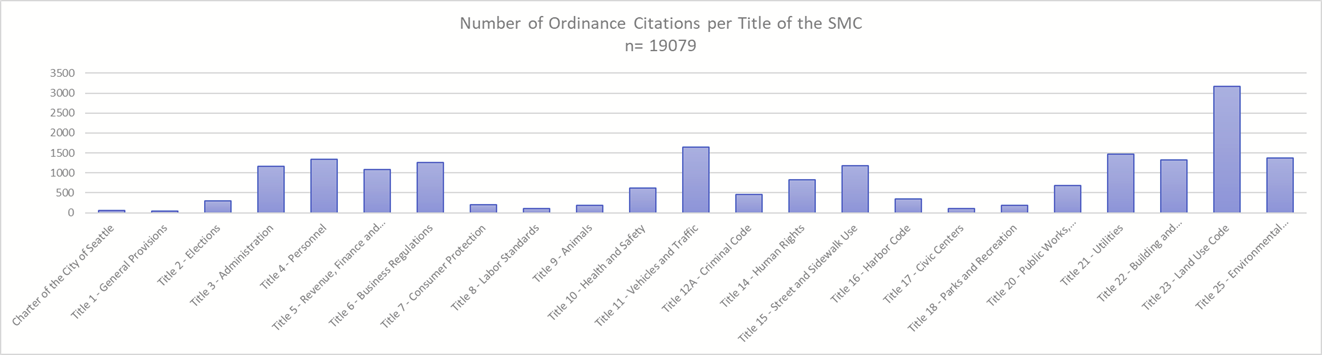

Ordinance citations in the Seattle Municipal Code denote that an ordinance has established or changed the section of the code in question. The more ordinances a single section cites, the more revision that section has undergone - often times because the code involves a fee or fine that changes with inflation. In total, I identified 19,079 citation citations across 8,867 sections, leading to a total rate of ordinances cited per section of 2.152. This gives us a very rough sense of whether a given Title or segment of the SMC is “variable” or “conserved”. The closer the “rate of ordinances cited per section” is to 1.0, the less it has undergone revision (the one citation being the law that establishes that part of the municipal code), and can be called a “conserved” region. The higher the “rate of ordinances cited per section” is, the more revision it has undergone, meaning that it is a “variable” region.

Variable titles, taken as a whole, include Title 4, Title 15 and Title 21, having rates of citation of more than 3 citations per section. If you were to imagine that as a single section of the municipal code, that would mean that section was re-written by new laws at least 2 times.

On the other end of the spectrum, Title 1, Title 8 and Title 10 have rates of ordinance citations that are close to 1, indicating that they may be “conserved” titles, unchanged since the ordinances that establish sections in these titles.

In plain language, the SMC can have parts that are either highly likely to change, or not very likely to change. Figure 1 displays ordinance citations bucketed into the different titles of the SMC (and the charter):

This is somewhat intuitive - legally governing a city would be very difficult if the basic rules of operation (such as in Title 1) were constantly changing. On the other hand, City Council has a responsibility to the people of Seattle to update laws and create new laws when appropriate, so you’ll see some subjects more subject to change.

Not all of the titles in the SMC are created equally, though - some of them have a massive number of chapters and sections, but some (like Title 1 that I mentioned) have only a small number of very important sections. This extends to the landscape within each title too - some chapters are longer and have more sections than others, and some chapters are more prone to a high number of ordinance citations than others.

Further analysis will take a look at the chapter structure and more finely define segments of the SMC that are ‘variable’ and ‘conserved’, as well as look at this variability over time to identify timeframes where regions of the SMC are more variable (such as when City Council is focused on a hot-button issue that demands multiple acts of legislation that influence a chapter of the SMC).

Figure 2 shows us that while there are limitations to looking at ordinance citations in the context of their broad Titles, there are patterns that emerge that suggest a link between variability and broad topic. Towards the center of the graph, there’s a stark change in the number of ordinance citations we see in Title 14 to Title 15, which is the change from “Human Rights” to “Street and Sidewalk Use”.

One would expect Human Rights to change less frequently than regulations related to Street and Sidewalk Use, which constantly update with the increasing complexity and further development of transportation infrastructure. The data supports this intuition, and the hope of looking at the data deeper is to uncover patterns that may not be so expected and understand why the patterns emerge as they do.

As I’m able to further refine the data by year and chapter, I should be able to clearly identify more significant patterns in the Seattle Municipal Code and incorporate these data into my model of the City of Seattle’s legislative history.

In future editions of TLB, I’ll produce some handy datasets that show us the Executive and Legislative administrations over Seattle’s history, having recently been to the Seattle Municipal Archives and received a boat-load of resources and help with identifying sources of historical data!

This week, we’ll loop back around mid-week to City Council Committees and the departments that they oversee. The best way to keep up with these conversations is to be a subscriber to The Lanyard Board, and to check out The Lanyard Board on social media.

The Lanyard Board is supported by readers like yourself. If you can, please support the project on Ko-Fi and tip the suggested amount of $2 for every month you feel a spark of enjoyment, insight or curiosity from The Lanyard Board.